Contents

The devastating Great Fire of 1910, consuming over 3 million acres across Montana, Idaho, and Washington, drastically altered the US Forest Service’s approach to wildfire management, shifting towards a policy of total fire suppression.

Alt: A raging wildfire consuming a forest, demonstrating the destructive power of uncontrolled wildfires like the Great Fire of 1910.

Alt: A raging wildfire consuming a forest, demonstrating the destructive power of uncontrolled wildfires like the Great Fire of 1910.

For centuries, Indigenous communities in the western US had practiced controlled burns to manage fuel loads and prevent large-scale wildfires. They understood the delicate balance of the ecosystem and the role of fire in maintaining its health. This traditional knowledge was initially considered by the newly formed US Forest Service in 1905. However, the events of 1910 would overshadow these practices.

The Big Burn: An Unprecedented Disaster

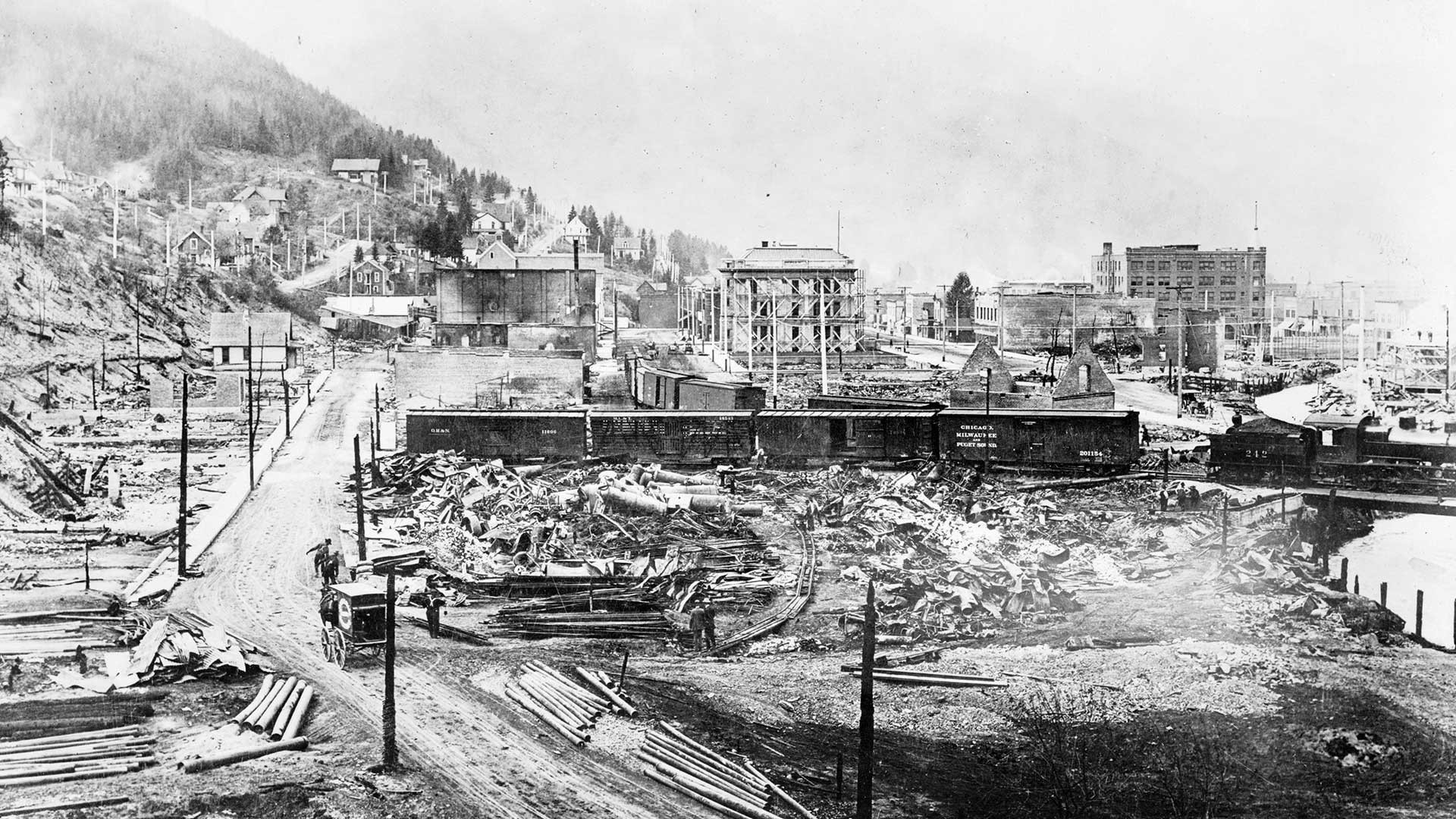

Destruction in Wallace, Idaho after the Great Fire of 1910.

Destruction in Wallace, Idaho after the Great Fire of 1910.

The Great Fire of 1910, also known as the “Big Burn” or “Big Blow Up,” remains the largest single wildfire in US history. On August 20, 1910, fueled by severe drought and driven by 70 mph winds, numerous small fires merged into a raging inferno. The fire swept across Montana, Idaho, and Washington, consuming an area larger than the state of Connecticut. Eyewitness accounts described tornado-like flames and “great red balls of fire” rolling up mountainsides.

The five-year-old US Forest Service, along with 4,000 deployed soldiers and thousands of firefighters, battled the blaze, but the fire’s intensity was overwhelming. Towns were leveled, and tragically, 87 people perished, including 78 firefighters. The smoke plume darkened skies as far east as New England.

The Rise of Total Fire Suppression

The immense devastation and loss of life from the Great Fire shocked the nation. The public demanded answers, and Congress responded by doubling the Forest Service’s budget. In the aftermath, the agency adopted a policy of “total fire suppression.” This policy dictated that all fires, regardless of size or location, were to be extinguished as quickly as possible. This approach prioritized immediate fire control over long-term forest health.

While some advocated for further research into controlled burns, the Forest Service dismissed these practices as too risky. The agency’s leadership, deeply impacted by the 1910 fire, viewed all fire as the enemy.

A Century of War on Fire

Alt: Members of the Civilian Conservation Corps fighting a forest fire in Washington state, circa 1937, highlighting the efforts in wildfire suppression during this era.

Alt: Members of the Civilian Conservation Corps fighting a forest fire in Washington state, circa 1937, highlighting the efforts in wildfire suppression during this era.

The decades following the Great Fire saw a militarized approach to wildfire management. The Forest Service, led by chiefs who had fought the 1910 fire, implemented strategies emphasizing rapid response and suppression. This included building access roads, constructing watchtowers, and employing thousands of workers through programs like the Civilian Conservation Corps.

The “10 a.m. policy,” introduced in 1935, mandated that all fires be extinguished by 10 a.m. the following day. This further emphasized the urgency of suppression and spurred the development of technologies like airplane surveillance and smokejumpers. Post-World War II, military technologies, including chemical fire retardants and satellite surveillance, were also incorporated into firefighting efforts.

Smokey Bear and Public Awareness

Alt: Smokey Bear, the iconic symbol of wildfire prevention, reminding the public of their role in preventing wildfires.

Alt: Smokey Bear, the iconic symbol of wildfire prevention, reminding the public of their role in preventing wildfires.

Recognizing the role of human activity in starting wildfires, the Forest Service launched public awareness campaigns. Smokey Bear, introduced in 1944, became the face of fire prevention, educating generations about the dangers of unattended campfires and careless behavior in forested areas.

Rethinking Fire Management

By the 1970s, the Forest Service began to reassess its total fire suppression policy. Research confirmed the ecological benefits of fire in certain ecosystems. Controlled burns, once dismissed, were recognized as valuable tools for managing fuel loads and promoting forest health. The agency started to incorporate “let-burn” policies in specific areas, acknowledging the natural role of fire.

Even Smokey Bear’s message evolved, shifting from preventing all forest fires to preventing unwanted wildfires. This change reflected a growing understanding of the complex relationship between fire and forest ecosystems. The Forest Service continues to adapt its strategies, grappling with the challenges of climate change and increasing human encroachment into wildland areas.